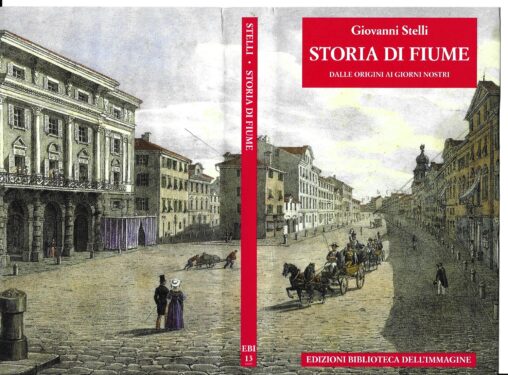

BRIEF HISTORY OF RIJEKA

by Giovanni Stelli

INTRODUCTION

The Adriatic, penetrating deeply between the Italian peninsula and the Balkan peninsula and approaching the passes of the Alps that lead to the Danube, forms at its north-eastern end the Gulf of Kvarner, Kvarner or Carnaro (in Croatian Kvarner), of which Rijeka is the most important city and port. In the ninth canto of the Inferno Dante highlights the position of Carnaro as the border of Italy, which he considers a “nation” within the Empire:

As in Arli, where the Rhone stagnates,

as in Pula, near the Carnaro

that Italy closes and its terminus […]

The city of Rijeka stretches along the sea. A karst watercourse – called over the centuries by different names, including Eneo (from the Latin Oeneus), Fiumara (especially in its terminal part), Recina and Rječina (in Croatian) – separated it from the Croatian town of Sušak until 1945.

Rijeka is the point of convergence of three easily accessible roads: to the north-west the road that connects it to Trieste, to the south-west that of the eastern coast of Istria and to the south-east that of the Croatian-Dalmatian coast. Geographically, the port of Rijeka is the outlet of a vast Croatian hinterland, along the Karlovac-Zagreb route, and Hungary, from Karlovac to Budapest. It is a position that corresponds to the opposite western end of Istria that of Trieste, connected to Vienna through the Slovenian and Carinthian-Austrian hinterland.

However, the lack of roads hindered the development of a commercial movement towards this hinterland until the eighteenth century, when the Via Carolina (1728) and the Via Ludovicea (1803) were built. The spread of railways in the second half of the nineteenth century further favored the mercantile development of the city, now permanently connected, by land, to Vienna via Ljubljana and to Budapest via Zagreb, and, on the sea, to the Italian Adriatic coast and Dalmatia up to the Bay of Kotor.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, in the period of the so-called “Hungarian idyll”, the centuries-old “vocation” of the city was thus fully manifested: to be a point of transit, hinge and synthesis between the continent and the sea, between different languages and cultures, always tenaciously maintaining its prevalent, but not exclusive, linguistic and cultural identity of an Italian character.

The awareness of this identity based on an idea of cultural nation, which had nothing to do with political affiliation, is the foundation of that municipal autonomy tenaciously claimed by the Rijeka people over the centuries: the city always refused to be incorporated into a province or intermediate political entity (such as Croatia) and claimed to depend directly on the central power of that Empire, to which she declared herself “most loyal”.

It was at the beginning of the twentieth century that, faced with the radicalization of the various nationalisms that undermined the structure of Austria-Hungary from within, the people of Rijeka began to see in the annexation to Italy a suitable solution to guarantee their linguistic and cultural identity.

But the Great War and the Peace Conference that followed did not lead to a harmonious coexistence between the various newly formed nations, but to great instability and acute conflicts. After a tormented period marked by D’Annunzio’s Enterprise and then by the failed experiment of the Free State, in 1924 Fiume was annexed to Italy.

The city’s political affiliation to the Italian state lasted only 23 years. Overwhelmed by the tragic events of the Second World War, Rijeka was occupied by Tito’s Yugoslav communist troops in 1945: subjected to harsh repression, within a few years it was emptied of 90% of its inhabitants and became the current Rijeka, a city in which the Italian Fiumani make up about 1.5% of 175,000 inhabitants.

1. FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE EIGHTH CENTURY A.D.: THE ROMAN TARSATICA

Since the Palaeolithic era, the territory in which the city of Rijeka later arose was inhabited, as evidenced by archaeological excavations. In historical times the name of this territory, which had Istria to the west and the Dalmatian coast to the east as its border, was Liburnia. The Liburnians, belonging to the largest population of the Illyrians, inhabited the eastern shore of the Kvarner and were mainly engaged in piracy.

It was to eradicate piracy in the Adriatic that the Romans waged war on the Illyrians and Histrians starting from the end of the third century BC. In the second half of the second century BC, Istria and Liburnia were already acquired by Rome.

Around the year 129 BC the so-called “Roman wall” was built, a fortified and garrisoned wall, which from Haidovium (today’s Audissina) went along the Karst plateau to near the current Rijeka, intended to separate the Iapidi from the Histri and to constitute a defense from any other invaders. Probably in this same period a fortress was built which became in the Augustan age the military colony of Tarsatica (Tarsactica), the Roman city “ancestor” of Rijeka.

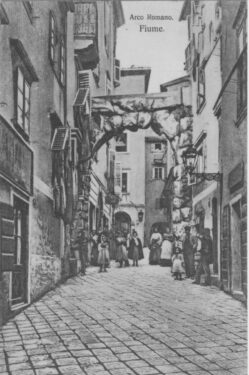

Tarsatica – a name of Celtic origin – stood on the right bank of the Eneus River. As evidenced by numerous archaeological finds, it was a city of some importance, with a forum, public buildings, a temple, a necropolis, baths and perhaps a theater. The only Roman monument still visible in the Old Town today is the so-called Roman Arch, probably a city gate. An evident affinity with Tarsatica has the current name of the locality of Trsat, seat of the famous sanctuary, located however beyond the left bank of the Eneus, where the Roman Tarsatica was located on the right bank of the river; It is not clear how to explain this circumstance.

Little is known about the events of Tarsatica in the imperial period. In the fifth century A.D. Istria and Liburnia were devastated by the raids of the barbarians. The reunification of the Empire by Justinian in 553 brought Tarsatica and Liburnia under Byzantine rule, but the Byzantines were unable to defend the Balkan frontier from the continuous invasions of barbarian populations, Huns, Avars and Slavs.

Between the end of the sixth and the beginning of the seventh century, the Avars arrived in the Balkan peninsula and on the shores of the Adriatic, followed by several tribes of Slavs, progenitors of Serbs, Croats, Slovenes and Bulgarians. The Croats occupied eastern Istria, Liburnia and Dalmatia, joining and mixing with the Latin population, which generally remained predominant in the coastal cities and islands, and converted to Christianity from the eighth century.

River: Roman arch (actually a Roman city gate)

2. THE MIDDLE AGES. RIJEKA WAS BORN: FROM THE DOMINION OF THE BISHOP OF PULA TO THAT OF THE DUINATI AND THE WALSEE

From the seventh century to the thirteenth century, almost total silence descended on the history of Tarsatica. Liburnia entered the sphere of Frankish rule and was incorporated into the Eastern March of Italy or March of Friuli, which in 828 was divided into four counties: Friuli, Istria, Carniola and Liburnia. According to a very late source, and therefore not very reliable, Tarsatica was destroyed by Charlemagne in 800. Other news has not reached us.

Only in the thirteenth century did the city that had once been Tarsatica emerge from obscurity, but its name changed: it is now designated as Flumen, Land of St. Vitus River, St. Vitus al Fiume, Sankt Veit am Pflaum, Rijeka, the latter translated in Croatian sources as Reka or Rika. San Vito is the name of the patron saint of the city, where already in the thirteenth century there was a church dedicated to the cult of this martyr saint, together with San Modesto and Santa Crescenzia.

From 1028 the city was enfeoffed to the bishop of Pula, who in 1139 ceded it to the counts of Duino, although it remained aggregated in terms of ecclesiastical dependence to the bishopric of Pula until 1787. The name of the Counts of Duino derives from the castle of Duino located at the mouth of the Timavo in the Gulf of Trieste and still existing.

In 1337 the Duinati, short of money due to the continuous wars and court expenses, ceded Rijeka to the Croatian dynasts Frangepani-Frankopan, counts of Krk and vassals of the Hungarian crown, who remained in possession of it for a period of almost thirty years. In 1365 the counts of Veglia returned the city to Hugh VI of Duino.

In the political game that affected the territories of the Upper Adriatic in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, the expansionist policy of Venice had become the most important political factor. To oppose the pressure of the Serenissima, the Duinati family established increasingly close relations with the Habsburgs: in 1366 they swore an oath of vassalage to the Habsburgs and supported them militarily in the subsequent war against Venice. The Duinate period of Rijeka lasted 260 years.

In 1399 the male branch of the Duinati became extinct and their possessions, including Fiume, passed to the House of Walsee, to whom the Counts of Duino were related, also closely linked to the Habsburgs. But, unlike the Duinati, the Walsee sought a friendly understanding with Venice, stipulating commercial and maritime agreements with the powerful neighbor.

In 1450 Lambert IV of Walsee was succeeded by his sons Lambert V and Vulgar III, who divided the hereditary possessions. In 1465 Volfango, to whom Fiume and Carsia had gone, designated Frederick III of Habsburg, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, as heir, and to the latter, a few years later, Rambert also alienated his hereditary possessions. With them the Walsee family became extinct and the Habsburgs came into possession of Fiume.

In the Duinate period Rijeka must have achieved a certain prosperity, mainly due to the transit trade between Italy and Carniola, a prosperity documented by the construction of new churches and buildings: in 1315 the Church of San Girolamo and the Augustinian Convent were built, around 1377 the bell tower was raised next to the Cathedral (or church of Santa Maria Assunta dating back perhaps to the eleventh century) and the latter was restored.

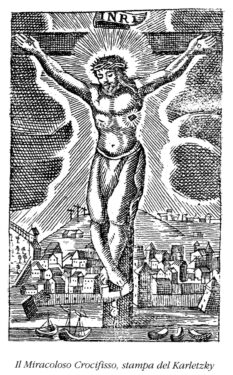

Of no less importance was the ancient church of San Vito, the patron saint of the city. In it was kept a wooden Crucifix, which will later be placed in the high altar of the current seventeenth-century church, against which, according to legend, a certain Pietro Lonzarich, in 1227 or 1296, enraged at having lost at the game, threw a stone: a stream of blood then came out of Christ’s side and the earth opened to swallow the sacrilege, leaving out only the guilty hand. This miracle would be at the origin of the construction of the church.

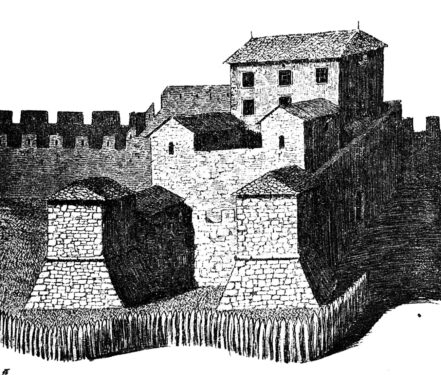

The development of Rijeka intensified in the fifteenth century in the Walsee period. The city, which extended to the east as far as the course of the Eneo, corresponded to the current Old City: it was surrounded by walls resting on the ruins of ancient Tarsatica, in which two gates opened, the “sea gate” in the place where today there is the Civic Tower and the “upper gate” on the opposite side, where today stands the bell tower of San Vito, and was dominated by the Castle erected on the ruins of the Roman fortress. The center was the Piazza del Comune, later called Piazza delle Erbe, where the Loggia stood, where the decisions of the Council and the sentences of the judges were issued.

The population of Rijeka then amounted to about 2000 souls and the city was divided into four districts or districts, whose names coincided with the names of the saints to whom the main churches were dedicated: the districts of Santa Maria (the Cathedral), Santa Barbara, San Vito and San Girolamo.

On an economic level, the fifteenth century marks the beginning of a rise for the city which, albeit with alternating phases, will continue in the following centuries, reaching its peak in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. As in the Duinate period, so in the Walsee period, iron, grain, timber and hides passed through Fiume from Carniola and Croatia; from Italy olive oil, wines and textiles. Of particular importance were the trades with the ports of the Papal States such as Ancona, while timber took the road to Venice. It should also be noted the presence in Rijeka of two shipyards and some minor industries.

We know that in the fifteenth century the Rijeka Commune had the right to administer itself in a relatively autonomous way, which led to oppose in some cases the claims of the feudal lord, represented in the city by the Captain who resided in the Castle. The most important body of the Municipality was the Council, made up of 16 or 18 notable and wealthy citizens, which elected the two Rector’s Judges, who administered justice together with the Captain. Among the other municipal magistracies, it is worth mentioning the Chancellor who was entrusted with the care of the archives and the Liber civilium, in which the public deeds and private deeds he drew up were recorded. The first of these books by the chancellor dates from 1436 and is written naturally in Latin.

The language spoken in the city by the majority of the people belonged to the Venetian koine (with borrowings from Croatian and Slovenian), as documented by the so-called fish tariff established by the Council of Rijeka on 10 January 1449 and reported in the Liber civilium of the chancellor de Reno, which states, for example,

that each person of what condition he wants to be or whether he wants to sell fish in the land of Fiume over in his distrito must sell the prexi infrascripti zoè the fish of the scales whether it is de livra or more if he has to sell de Easter even to San Michele at one and a half the livra grosso and from S. Michele even to take to s. dui and Lent at two and a half money.

[…] item that the palamides if they must sell for money 1 the livra digging out the entrails […]

The Croatian Chakavo dialect was spoken in the surrounding area, which in the city statute of 1876 was called “Illyrian” for the purposes of public education.

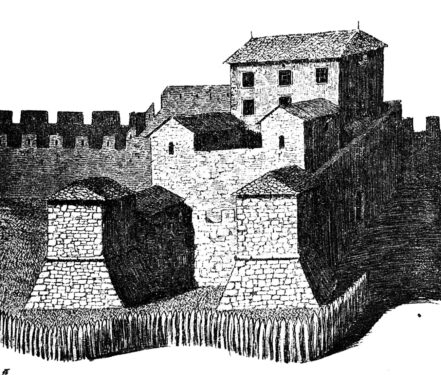

Medieval Rijeka – The Castle (no longer existing), drawing by Riccardo Gigante from the early 900s (Historical Museum Archive of Rijeka in Rome)

Medieval River – Barbicans, drawing by Riccardo Gigante from the early 900s (Historical Museum Archive of Rijeka in Rome)

Medieval Rijeka – Village, drawing by Riccardo Gigante from the early 900s (Historical Museum Archive of Rijeka in Rome)

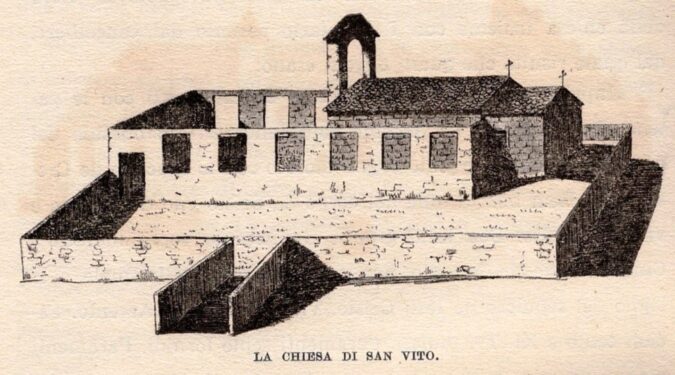

The old church of San Vito which in the second half of the seventeenth century was replaced by the current one

The Miraculous Crucifix, print by Karletzky

3. FIUME IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: BETWEEN VENICE, THE HABSBURGS AND THE USKOKS

In 1453 the Turks had conquered Constantinople (Byzantium), ending the existence of the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire. In the following years they had penetrated the Balkan peninsula, taking possession of Bosnia-Herzegovina (1463) and then Serbia (1496). In 1526 part of Hungary, including Buda, also fell under the rule of the Turks, who in 1529 came to besiege Vienna, although they were unable to conquer it. Dalmatia and Rijeka were under constant threat, which in fact strengthened its defenses.

The Habsburgs and Venice had a common enemy in the Ottoman Empire, but also opposing interests both in the Adriatic area and in the territory of Gorizia. So in 1508 they entered the war and on May 27 the Venetians occupied Fiume, which remained under the dominion of the Serenissima for just over a year. In May 1509 Venice, defeated at Agnadello during the war of the League of Cambrai, was forced to withdraw from Fiume. In retaliation, the Venetians bombarded Fiume from the sea on 2 October 1509 and sacked it.

Fiume had already been sacked by Venice in 1369 during the Duinate period, but the sacking of 1509 was much more destructive to the point that the Venetian captain Angelo Trevisan wrote in a letter: “Et mai per lui non se dice qua sono Fiume ma qua sono stato Fiume!”. A final devastation of the Kvarner city by Venice would have occurred in 1511, but we know little about it.

Fiume was always hostile to Venice: the Venetians “know from experience that when a Rijeka is born, a capital is born that is an enemy of the Venetian name“, so we read in a letter of 1604 addressed by the Rijeka Council to the Archduke of Austria. To the Habsburgs, on the other hand, the Kvarner city remained “very loyal“, as Emperor Maximilian had written in 1515 in a letter to the Council and the people of “our land of Rijeka“.

Rijeka’s hostility towards Venice was also manifested in the Uskok affair. Those who fled from the Bosnian and Dalmatian hinterland in the face of Turkish pressure were called Uskoks (from the medieval Croatian uskok which means fugitive) on the coast. Settled in Segna, the Uskoks practiced piracy on the sea, at first to the detriment of the Turks and then also of Venice, encouraged more or less openly by the Habsburgs.

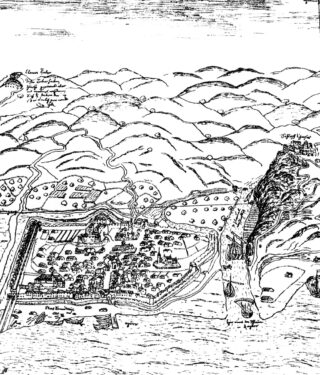

Officially, the Rijeka authorities always denied any relationship with the Uskoks, but in reality they had complicity and help in Rijeka: in a map of the city of 1671 there is a “Hosteria where the Scocchi stay” in a place just outside the walls!

In the “War of Gradisca” (1615) between Venice and the Habsburgs, Rijeka once again sided with the Uskoks against Venice, but the Peace of Madrid in 1617, which put an end to the conflict, also marked the end of the Uskoks who were dispersed in the Croatian hinterland. The final treaty was signed on 8 August 1618 in the Castle of Fiume and in the presence of Captain Stefano della Rovere.

At the end of the sixteenth century the population of Rijeka reached 3000 inhabitants. The economic situation of the city suffered a certain deterioration both because of the Habsburgs’ choice to favor Trieste, and because of the Turkish danger.

The weight of the Italian language and culture increased over the course of the century, while the Croatian cultural presence in the city is documented by the presence of a typography in Glagolitic script (1530).

4. THE FERDINDEAN STATUTE OF 1530: THE AUTONOMY OF FIUME

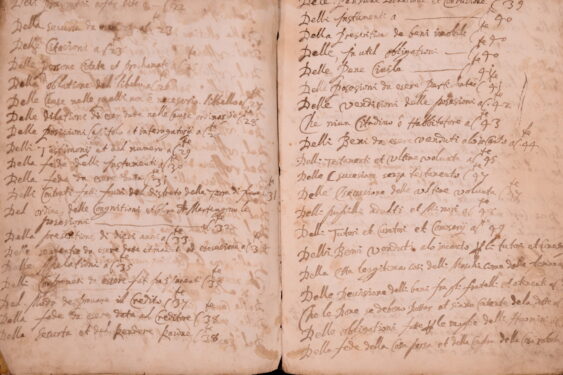

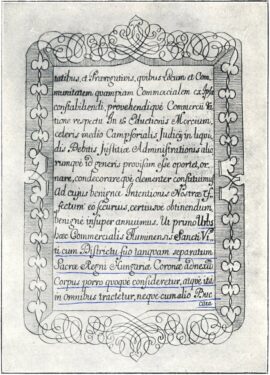

On 29 July 1530, Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg ratified the Statute of the City of Rijeka with a sovereign letter patent. Drawn up by the Ferrara Goffredo Confalonieri, the Ferdinand Statute confirmed the centuries-old franchises of Rijeka. The text is in Latin, but there is a contemporary manuscript version written in Italian, preserved in the original in the Historical Museum Archive of Rijeka in Rome.

The Statute is divided into four books: the first deals with the organization of the Municipality, the second with the procedure in civil cases, the third with the procedure in criminal cases and the fourth with the “extraordinary things”, i.e. provisions on various matters.

The already existing system of the Municipality was substantially confirmed.

The representative of the Sovereign, by whom he was appointed, was the Captain: he lived in the Castle together with a small garrison and presided over the Council. The Captain’s lieutenant was the Vicar, appointed by the sovereign until 1574 but then elected by the Council.

The self-governing body of the city was the Major Council, composed of 50 people, which elected a Minor Council of 25 members. The Consiglio Maggiore was a de facto hereditary body which was entered by birth and co-optation and the councillors constituted the city patriciate . The two Rector Judges were the most important magistrates: one was appointed by the Captain within the Minor Council and the other was elected by the Major Council. Among the other magistrates, the Chancellor and the Mayors should be mentioned. The Chancellor, appointed by the Council, had the task of keeping all public and private records and drawing up the minutes of the Council. The Mayors, elected in number three by the Major Council, controlled the work of the magistrates including the Vicar.

The Ferdinandean Statute remained in force until the beginning of the nineteenth century and the people of Fiumani constantly appealed to it against attempts to limit the autonomy of the city, which already in the sixteenth century was, similarly to Trieste, an immediate city, that is, not annexed to any province, but directly dependent on the central power. In fact, while in general the cities of the House of Austria paid homage to the Sovereign united with the province to which they belonged, Rijeka, like Trieste, enjoyed the privilege of paying homage separately. This particular position is also documented by the fact that Fiume in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had its own consuls, appointed by the Council, in various Italian cities, such as Ancona, Barletta, Manfredonia, Civitavecchia and Messina.

The city lost this right in 1748, when, within the framework of the policy of enlightened absolutism, the Mercantile Province of the Littoral was established.

Two pages of the Ferdinand Statute of 1530 in the contemporary Italian version (original kept in the Historical Archives of Rijeka in Rome)

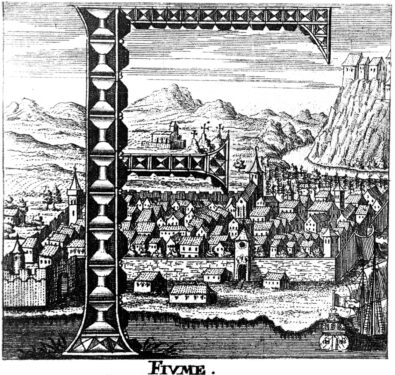

River in a print from 1579

5. FIUME IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY: TURKISH DECLINE AND REBIRTH OF HUNGARY

During the seventeenth century there was a progressive decline of the Ottoman Empire, and, connected to this decline, the rebirth of the Kingdom of Hungary.

In 1683 the Turks failed to conquer Vienna for the second time, defeated by the Polish king John Sobieski. As in much of Europe, the Council and the Captain also organized grandiose celebrations in Rijeka for the victory “not heard in centuries against the common Ottoman enemy”, as stated in the minutes of the Council.

On September 2, 1686, Archduke Charles’ imperial army captured Buda, the Hungarian capital that had been subject to Ottoman rule for a century and a half. This victory was also celebrated in Rijeka with religious ceremonies, illuminations, dances and wine distributions. The successes of the imperial army, led from 1697 by Eugene of Savoy, multiplied. Transylvania was reunited with Hungary and Leopold I of Habsburg also became King of Hungary.

The Peace of Carlowitz of 26 January 1699 sanctioned the definitive decline of the Ottoman Empire and at the same time marked the return to the European scene of Hungary, reunified under the scepter of the Habsburgs. With the subsequent Treaty of Passarowitz in July 1718, Austria further expanded its dominions in the Balkan peninsula at the expense of the Turks: Hungary regained all its ancient territory, from the Carpathians to the lower Danube, including Rijeka, intended to serve as a port of call for the products of the Hungarian crown area.

The most important event in the cultural history of Rijeka in the seventeenth century was the opening in 1627 of the Jesuit College, to which the municipality gave an annual subsidy and entrusted the church of St. Roch. The subjects of study were Latin, Greek, history, religion, geography and arithmetic. In the upper classes the language of instruction was Latin and in the lower classes Italian. The pupils came not only from Rijeka, but also from Carniola, Istria, Dalmatia and also from the Austrian provinces, and were of mixed nationality (Italian, Croatian, Slovenian and Austrian). In the last years of the seventeenth century theirs amounted to over 150, a considerable number, if you think that the city had about 3000 inhabitants. The Jesuit College, which had a flourishing life until the suppression of the Order in 1773, was an effective instrument for cultural promotion and the dissemination of the Italian language in the city and even beyond the city walls.

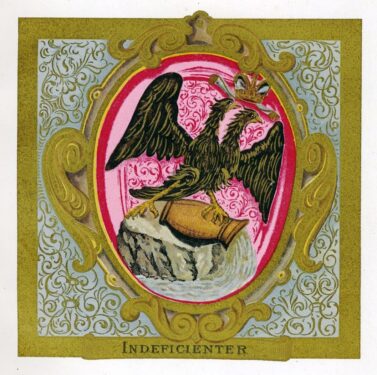

During the century, the city’s autonomy was consolidated against various attempts to limit it made above all by some Captains in opposition to the Council. To confirm this autonomy, on 6 June 1659 Emperor Leopold I granted Rijeka the right to a coat of arms and a banner. Until then, the image of St. Vitus was on the seal of the city, while the coat of arms of 1659 is a double-headed imperial eagle turned to the left with its left paw placed on a vase from which water comes out, and with a card underneath that bears the inscription Indeficienter (inexhaustibly, endlessly, referring to water and the city’s loyalty to the Habsburgs). In memory of the previous seal, the Municipality used the Leopoldine coat of arms, often flanked by Saints Vito and Modesto. From the colors of the coat of arms – carmine red of the field, golden yellow of the frame and ultramarine blue of the background – came the flag of Rijeka, a tricolor with horizontal bands with the colors arranged from top to bottom in the order mentioned.

Inthe second half of the seventeenth century the population of Rijeka exceeded 3000 inhabitants and there was an improvement in the economic situation, as is demonstrated by the fact that some Italian merchants settled in Rijeka with their families, such as the Cremonese Benzoni, the Apulian Bono, the Istrian De Franceschi, the Venetian Orlando.

In the architectural aspect of the city there were important innovations. The great Captain Stefano della Rovere had the castle rebuilt, entrusting its construction to the painter and architect Giovanni Pietro Telesphoro de Pomis from Lodi, who was also active in Trsat. In place of the ancient church of San Vito, the Jesuits had a new large circular church built that resembles that of the basilica of Santa Maria della Salute in Venice; the works, under the direction of Francesco Olivieri, lasted from 1638 to 1744. In 1632 the first bridge over the Eneo was built.

Finally, some prominent ecclesiastical personalities should be remembered such as the bishop of Segna and Modrussa Giovanni Agalich (1588-1649), who collaborated with the Franciscan theologian and man of letters, author of important works in Latin, Italian and Croatian, Francesco Glavinich (1585-1652) and Pietro Mariani (1611-1665), a man of profound doctrine and diplomat, who stood out for his work aimed at improving the customs and education of the clergy.

Seventeenth-century map of Fiume dedicated to Baron Pietro de Argento, captain of the city from 1672 to 1694

Coat of arms of Rijeka granted by Emperor Leopold I on 6 June 1659

6. RIJEKA IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: FREE PORT AND "SEPARATE BODY" ANNEXED TO HUNGARY

With the Pragmatic Sanction, issued by Emperor Charles VI in 1713, the principle of succession to the throne was introduced into the Habsburg monarchy also through women. All the states and provinces of the Empire were called upon to approve it and in 1720 the emperor also urged the “faithful, dear Judges and Council of the City of Rijeka” to this end.

A year earlier, with the patent of 18 March 1719 , Charles VI had established Fiume as a free port (together with Trieste). The port of Rijeka was granted important privileges, such as customs exemption for incoming and outgoing ships, and so the traffic of Rijeka, until then almost exclusively Adriatic, soon expanded to become Mediterranean.

Charles VI also provided for the strengthening of the access roads to the city: the road to Germany was widened, which connected Rijeka to Austria through Slovenia, and in 1726 the Carolina road (so called in honour of the Sovereign) was built, which connected Rijeka to Hungary through Croatia. The road system was completed in 1760 with the construction of the Giuseppina road, a side branch of the Carolina, which led from Bogliuno d’Istria to Kastav and then to Rijeka.

These measures strengthened Rijeka’s link with Hungary. In 1771 Rijeka “could already be considered essentially as a Hungarian port, since in that year its exports consisted of two-thirds of Hungarian goods, and only one-third of goods of Austrian origin” (Alfredo Fest).

In 1748, in order to unify the administration of the different municipalities of the Liburnian and Istrian coasts, Empress Maria Theresa, who succeeded Charles VI in 1740, established the Mercantile Province of the Littoral, dependent on an Intendenza that had its headquarters in Trieste, and Rijeka was also assigned to the new Province. The Hungarians, the Croats and of course the Rijeka protested against the centralization of maritime trade in Trieste.

Maria Theresa then issued the rescript of 14 February 1776: the administration of Rijeka was the responsibility of Hungary through the Council of Zagreb, i.e. through Croatia. Fiume was thus finally removed from the competition of Trieste, but the fact that the annexation to Hungary was carried out through Croatia aroused the clear opposition of the people of Rijeka. The Council protested and demanded that the city, which had always been “considered a separate province”, be annexed directly to the Kingdom of Hungary.

After more than a year of disputes, Maria Theresa retraced her steps: the Diploma of 23 April 1779, annexed to a new rescript, modified the situation in the direction desired by the people of Rijeka, establishing that this commercial city of Fiume S. Vito with its district must also be considered for the future as a separate body, annexed to the crown of the Kingdom of Hungary, and so it is to be treated in all respects and not to be confused in any respect with the district of Bakar which has belonged to the kingdom of Croatia from its beginnings.

The particular position of Rijeka as an “immediate city” was thus reaffirmed and strengthened, i.e. a body separate from any other province.

The Diploma of 1779 was however the subject of conflicting interpretations, giving rise to a historical-legal controversy that lasted over a century between Rijeka and Hungarians on the one hand and Croats on the other.

The policy of Maria Theresa and her successors, called “enlightened despotism”, promoted the economic development of Rijeka, but also led to a limitation of municipal autonomy. Although without questioning the Statute of 1530 and despite the Diploma of 1779, important attributions, such as the prerogative of appointing consuls, were taken away from the Council and the Municipality was subjected to greater control by the State.

In the eighteenth century, and especially in the years 1776-1809, i.e. in the first Hungarian period of Rijeka, the city experienced a remarkable development in various aspects, starting with the demographic: the population went from 5,132 to 8,958 souls with an increase of over 74%. Immigration from Istria, Friuli and Croatia increased. In 1733 some families of Serbs and Greeks of the Orthodox religion settled in Rijeka and in 1786 the Greek Church of St. Nicholas was built. Rijeka citizenship was conferred with generosity, because – as we read in a Council document of 1795 – “the advantage of a free maritime commercial city is to have numerous the People”.

The road system was strengthened with the construction (1803-1809) of a new, more modern road, parallel to Via Carolina, the Via Ludovicea. This favored the development of trade and was accompanied by the birth of new industrial activities: in 1750 a sugar refinery plant was built that employed over 700 people.

From 1775 Rijeka began to extend outside the city walls: new buildings were built along the sea and on the slopes of the hills. In 1722 the Lazzaretto was built, since the development of maritime traffic led to the arrival of ships from ports at risk.

The Palazzo del Governo (1780) and numerous other works in the “Baroque” style were built by the Trieste architect Antonio Gnamb, who worked for several years in the city together with other Italian architects and sculptors, such as the Treviso Minnini who designed the administration building of the Sugar Refinery in Baroque-Classicist style (1786).

In 1778 Rijeka had its first permanent printing press and a publishing house founded by Lorenzo Karletzky from Bohemia. Among the men of culture of Rijeka of the period should be remembered Giuseppe Bardarini, historian and author of important theological treatises, Giuseppe Zanchi, author of philosophical, theological, historical and scientific works; Francesco Saverio Orlando, erudite and polyglot, the preachers Ludovico Bajelardo and Giuseppe Francesco Spingaroli.

In the second half of the century an important medical school was formed in the city, at the instigation of Saverio Graziano, originally from Barletta and who became the city’s protophysician in 1740. In 1786 a School of Obstetrics was opened by the Rijeka surgeon Giacomo Cosmini. Nicolò Host, one of the greatest botanists of the time (Austrian Flora, 1827), was also a doctor by training.

Diploma of Maria Theresa of 1779 in which Rijeka is recognized as a “separate body annexed directly to the Crown of Hungary”

7. THE FRENCH PERIOD (1809-1813) AND THE RETURN TO HUNGARY IN 1822

The French Revolution of 1789 and the war between France and the countries of the European coalition that broke out in 1793 did not produce significant effects on the life of Rijeka. But in 1796 the war affected northern Italy: the French attacked the papal cities of Ferrara, Bologna and Ancona, in March 1797 they entered Trieste and on 5 April occupied Fiume for a few days. With the Treaty of Campoformio (October 1797), which marked the end of the Republic of Venice, Rijeka continued to depend on the Austrian Empire, while Istria and Dalmatia passed to the French.

On 14 October 1809 with the Treaty of Schönbrunn Rijeka was ceded to France by the Empire of Austria – the title of Emperor of Austria had been assumed in 1804 by Francis II, who had thus put an end to the centuries-old existence of the Holy Roman Empire, becoming Francis I of Austria – and until 1813 it was part, within the Napoleonic Empire, of the Illyrian Provinces, a state that stretched from the Austro-Bavarian border to the Bay of Kotor. Rijeka thus came to depend again on Croatia and the city statute was abolished: on 7 March 1812 the new municipal council met chaired by the French-appointed maire or burgomaster, Paolo Scarpa. But, after a few months, in 1813, with the defeat of Napoleon in the Russian campaign, the Kvarner city returned to the Empire of Austria.

The municipal authorities of Rijeka, in a report to the Austrian government on October 27, 1813, drew a completely negative balance of the “inhuman French government”: a “deadly” taxation and “burdens of all kinds, almost inconceivable” had reduced the city to exhaustion. This explains the triumphal welcome given by the people of Rijeka to the Austrian general Laval Nugent, who entered Fiume at the end of August 1813.

The enthusiasm of the people of Rijeka for the return of the Austrian Empire, however, soon turned into disappointment: the city was not reincorporated into Hungary, did not see its municipal freedoms restored and continued to decline economically.

Finally, on 5 July 1822 , Emperor Franz I proclaimed his decision to return part of the Austrian Littoral with Rijeka to the Kingdom of Hungary. The decision aroused great joy in the people of Rijeka who joyfully welcomed Count György Majláth on 15 October 1822, who had come to the city to take it over in the name of the Hungarian Government: a choir of girls sang a hymn composed for the occasion in which it was said:

Now that we have returned / To the Kingdom of Hungary / Let each one be happy / And rejoice in the heart; / And to his beloved King / Who wise governs him / We swear eternal faith, / We swear eternal love.

The conditions prior to 1809 were restored with the Hungarian Littoral ruled by a Hungarian governor based in Rijeka and the administration of the city entrusted again to the City Council composed of 50 patricians. The period 1822-1848 constitutes the second Hungarian period of Rijeka, characterized by a renewed economic impetus and significant cultural development.

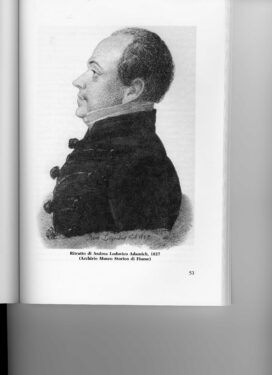

A great protagonist of the city’s renewal was Andrea Lodovico de Adamich (1767-1828): convinced that the economic future of Fiume depended on trade with the towns of the Danube basin, he gave life to several important entrepreneurial initiatives, including the foundation of a paper mill on the Eneo, later purchased in 1828 by Walter Smith, brother of the economist Adam, and Charles Meynier. Active in politics – he represented the city in 1822 at the Congress of Verona of the Holy Alliance and in 1825 at the Diet of Pressburg – he also contributed to the cultural development of Rijeka, designing and having a large theater built at his own expense, called Adamich in his honor (which was replaced in 1885 by the monumental Teatro Verdi).

Also worth mentioning are Gasparo Matcovich (1797-1881), entrepreneur and politician, to whom we owe the arrival in Fiume of Robert Whitehead, the creator of the Torpedo Factory, and Iginio Scarpa (1794-1866), son of Paolo who had been maire in the French period, to whom the tourist enhancement of Opatija dates. Finally, it is worth mentioning Count Laval Nugent von Westmeath, the liberator of the city in 1813, who, with Adamich’s help, bought and restored Trsat Castle, making it the family tomb and founding a museum there in 1843.

After a slight decline in the years 1810-1822, the population of Rijeka continued to grow, reaching 11,867 inhabitants in 1847.

In 1831 the project for a major expansion of the port was drawn up, but it was not carried out and improved until the second half of the century. The advent of rail transport put the construction of a railway line between Rijeka and Budapest on the agenda, which was also destined to be built in the years following the uprisings of 1848.

Industrial activity experienced considerable impetus. In 1851 the government bought the building of the old Sugar Refinery (closed in 1820) and inaugurated the new large tobacco factory. Smith and Meynier’s paper mill has already been mentioned: the large plant, located on both banks of the Fiumara about four kilometers from the city center, exported high-quality paper not only to Austria, but also to England and Brazil. In 1841 on the slopes of the mountain that leads to the valley called Žakalj, a grandiose flour factory was built (which in 1886 milled an average of 500 quintals of grains per day). The traditional shipbuilding industry also made a vigorous recovery: ships built in Rijeka were sought after in all countries, including America, and brought the city a profit of almost two million francs a year.

Several public utility works were established such as the General Institute for the Poor , also known as the Branchetta Institute, because it was financed by the brothers Antonio and Costantino Branchetta, merchants. In 1823 the new hospital was inaugurated; in 1833 the new Lazzaretto of San Francesco in Martinschizza was completed and in 1841 the Kindergarten of Charity for Children was founded.

In the development of the city’s cultural life, an important role was naturally played by the Theatre founded by Adamich, as well as by some private associations, including the Merchants’ Casino , which opened in 1806 and took the name of the Patriotic Casino in 1848. In 1813, in the printing house founded by Lorenzo Karletzky, which had taken the name of “Karletzky Brothers”, the first Rijeka newspaper Le Notizie del Giorno, the biweekly periodical l’Eco del Litorale ungarico (from 5 April 1843 to 4 April 1846) and other newspapers and magazines were printed.

In the field of medicine, the figure of Giovanni Battista Cambieri (1754-1838) should be remembered: born in 1754 near Pavia, he moved to Rijeka in 1797 where he carried out his activity as protophysician of the Littoral for 41 years, studying in depth the so-called Škrljevo disease, which raged especially in the rural areas of the area, and correctly classifying it as a form of syphilis to be treated with mercurial compounds. Cambieri was also a great philanthropist: for decades he covered the expenses for the care of the poor with his patrimony, which at his death he left entirely to the hospital where he worked.

A bust of Cambieri was sculpted in 1840 by the Rijeka sculptor Pietro Stefanutti (1822-1858), one of the protagonists of the Rijeka artistic life of the time. Also worth mentioning are the painters Francesco Colombo – who died at the age of twenty-three in 1843 and of whom few but significant works remain –, Alberto Angelovich (1822-1849), Marco Chiereghin (1777-1831) and above all Giovanni Simonetti (1817-86).

On May 9, 1821, a music school was opened under the direction of Wenceslas Wenczel and Joseph Prohaska. When Wenczel died in 1835, the management was taken over by Giovanni Zaytz, who in turn was replaced by his son Giovanni. Giovanni Zaytz jr (1832-1914) studied composition at the Milan Conservatory and in 1860 had his opera Amelia performed in Rijeka. Appointed director of the Zagreb Opera House in 1869, he devoted himself to composing a series of operas inspired by Croatian national history.

Anonymous pamphlet published in Rijeka in 1823 to celebrate the reincorporation into the Kingdom of Hungary (Rijeka Historical Museum Archive in Rome)

8. THE CROATIAN PERIOD 1848-1869

The European political order established by the Congress of Vienna was upset by the national-liberal movements. In 1848 they affected most of the European countries and in particular Italy and Hungary within the Austrian Empire.

In March 1848 Emperor Ferdinand I, who succeeded Francis I in 1835, appointed General Josip Jelačić, a supporter of the Triregnum , i.e. the union of Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia within the Empire, as ban of Croatia, and on 3 June 1848 the Diet of Zagreb declared that it considered Croatia to be free from any juridical-administrative link with Hungary and that it “retained the districts of Rijeka, Buccari the seafarer or of Vinodol integral parts of the Triregnum”.

So on August 31 Rijeka was occupied by the Croatian troops of Josip Bunjevac, in the name of the ban of Croatia Jelačić and the Hungarian governor Erdödy had to abandon the city. On the same day, Bunjevac informed the Municipal Council of his intention to preserve “intact your municipal prerogatives, as well as your city institutions” and “the use of the Italian language“.

However, the Council protested against the arbitrary military occupation and sent a complaint to Jelačić in Zagreb, complaining about the lack of respect for the “universally used Italian language”, despite Bunjevac’s declared intentions.

In August 1849 the Hungarian Revolution ended in complete defeat and Austrian policy embarked on the path of a harsh absolutist restoration. This orientation changed after the unfavorable outcome for Austria in the war of 1859. In October 1860, Emperor Franz Joseph decided to restore an autonomous role to Hungary, thus opening up the prospect of re-annexation to the Hungarian Kingdom for the people of Rijeka.

The Council of Rijeka exerted continuous pressure on the emperor in this regard, referring to the Teresian Diploma of 1779 and denouncing on 31 January 1861 the policy of the Croatian authorities hostile to the “Italian language, which is also the one that has been spoken since Rijeka existed”. In April of the same year, called to elect their deputies to the Diet of Zagreb, the people of Rijeka overwhelmingly wrote “nobody” on the ballot!

Defeated in the war against Prussia in 1866, Austria finally decided to adopt partial decentralization. On 12 June 1867, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (Ausgleich) came into force: Hungary acquired an equal status with Austria and the Empire – which became Austro-Hungarian or Dual Monarchy – was divided into two parts united by the dynastic bond (and by three ministries in common): Cisleithania with Vienna as its capital and Transleithania with Budapest as its capital.

The question of Rijeka was also on its way to a solution: on 5 April 1867 , on the proposal of the Hungarian government, Edoardo de Cseh was appointed Extraordinary Commissioner of Rijeka, and was triumphantly welcomed by the people of Rijeka on 7 May. With this the Croatian rule ended and the link between the Kvarner city and Hungary was re-established. With the rescript of 26 May 1867 Rijeka had the right to a seat in the Hungarian Diet and in June of the same year the Rijeka elected the Hungarian Ákos Radics as deputy, who had promised to defend the city’s autonomy “and the only possible language for Rijeka, Italian”. Thus began the third Hungarian period of Rijeka, which will be discussed in the next chapter.

During the Croatian period, the population increased from 11,865 souls in 1847 to 17,884 in 1869.

In terms of commercial traffic , there was a setback, due to the absolutist-centralist orientation of Austrian policy, which, aimed at favoring Trieste, neglected the port works planned and begun in the second Hungarian period and the development of railway lines to Croatia and the Hungarian plain.

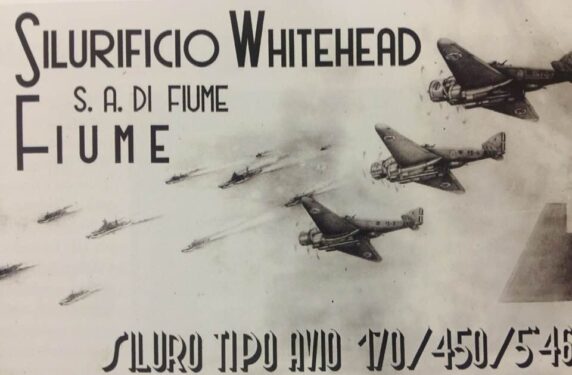

The crisis, on the other hand, spared the Rijeka industry (whose volume was equal to 50% of that of the industry of the whole of Croatia). The shipbuilding industry continued to develop, as did the Chemical Products Factory of the Rijeka Limited Company led by Walter Crafton Smith, the Metal Foundry – inaugurated in 1855, which would take the name of Technical Plant and in whose place the Whitehead torpedo factory would later be built – , the Tobacco Factory, which became the largest manufacture in the sector throughout the Empire, the Paper Mill, which exported paper all over the world, etc.

Industrial dynamism corresponded to a development of the banking sector. In 1855 the branch of the Austro-Hungarian Bank was opened in the city and on 1 January 1859 the local Cassa Comunale di Risparmio was established, which from 1859 to 1886 recorded a constant increase in capital and in the number of depositors.

On 1 August 1852 gas lighting was introduced in the city, in 1855 the telegraph line between Rijeka and Trieste was opened and in 1858 the one between Rijeka and Senj. The two banks of the Fiumara were joined by a new iron bridge.

On 26 March 1856, Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian laid the foundation stone of the large building of the Naval Academy, which was solemnly inaugurated on 4 October of the following year.

As far as education is concerned, women’s education had a great boost. with the creation of several specific institutes from elementary to high school.

The Croatian cultural and political presence was of great importance in this period. Ljudevit Gaj, the founder of Illyrianism, moved the editorial office of his magazine Neven to Rijeka, and the most important Croatian intellectuals of the time taught in the city’s Croatian gymnasium. In 1855, the Narodna čitaonica riječka, the Croatian People’s Reading Hall, was opened. From 1861 to 1866 Ante Starčević lived in the Kvarner city, founder together with Eugen Kvaternik of the Croatian Party of Law, who was in close relations with Erazmo Barčić (1830-1913), an opponent of the autonomists in the name of an organic Croatian nationalist vision, which had one of its models in the Italian Risorgimento.

The Italian people of Rijeka opposed Croatian nationalism with a defence of Italianness on a linguistic and cultural level, while on a political level the “patriotism” they professed was unquestionably Hungarian. Uncompromising defense of municipal autonomy and Hungarian political loyalism: this position was supported by the city press, such as the Eco di Fiume, which appeared in 1854, and La Bilancia, a weekly and then daily founded in 1867 by the publisher and writer Emidio Mohovich.

Arguing this autonomist position on a scientific level was the task of Rijeka historiography, whose birth certificate dates back to the decision taken by the Rijeka Municipality on 3 July 1848, when the Croatian occupation of Rijeka was already in the air, to appoint a five-member historical commission to defend with a documented investigation “the rights [della città] of established by the Teresian Diploma of the year 1779 and subsequent related laws”. Giuseppe Politei, Ludovico Giuseppe Cimiotti, Girolamo Fabris, Giovanni Kobler and Pietro Rinaldi were called to join the Commission. The immediate result of this decision was the Rijeka Almanac, published annually from 1855 to 1860 by Politei.

One of the members of the Commission, the erudite Ludovico Giuseppe Cimiotti left unpublished a history of Fiume in six volumes written in Latin and entitled Publico-politica Terrae Fluminis S. Viti adumbratio historice ac diplomatice illustrata.

9. THE "HUNGARIAN IDYLL"

With the rescript of 7 November 1868 , Franz Joseph confirmed the position of Rijeka as a “separate body attached to the Holy Hungarian Crown” and invited the Hungarian Diet, the Croatian Diet and the city of Rijeka to elect their own deputations in order to reach a definitive agreement on the legal position of the city. The three deputations, however, failed to reach an agreement, limiting themselves to proposing a temporary solution, the so-called Provisorium, which never became definitive and remained in force until the collapse of the Empire in 1918!

The rescript of 28 July 1870 sanctioned the provisions of the Provisorium: the Governor of Rijeka and the Hungarian-Croatian coast, appointed by the king, was the intermediary between the Municipality and the government of Budapest and had political control of the city and the district, the administration of which was instead the responsibility of the City Hall on the basis of a Statute to be issued by the city itself.

Governor József Zichy took office on 14 December 1870 and on 7 April 1872 the Statute of the Free City of Rijeka and its district, drawn up by a Municipal Commission, was approved by the Hungarian government. In the Statute of 1872, Rijeka explicitly presented itself as a third factor on a par with Hungary and Croatia, so much so that in his official communication Governor Zichy recalled the principle of self-determination of the city: nihil de nobis sine nobis.

The Municipal Representation, i.e. the Council, composed of 50 councillors for the city and 6 for the district (the sub-municipalities of Plasse, Cosala, Drenova), lasted in office for six years and the Podestà was elected from among it.

The years 1869-1896 constitute the period of the so-called Hungarian idyll: close economic, social, political and cultural ties were established between Rijeka and Hungary. Through Rijeka, the interest of Hungarians in Italian culture intensified. The people of Rijeka, in turn, contributed to the spread of Hungarian literature in Italy: among the translators from Hungarian we must mention Pietro Zambra, Ernesto Brelich, Francesco Sirola, Silvino Gigante. Even after the dissolution of the Empire, this tradition continued in the twentieth century with Enrico Burich – translator in 1931 of the novel The Boys of Pál Street by Ferenc Molnár –, Antonio Widmar, Paolo Santarcangeli and Ignazio Balla, and with the Italian magazine Corvina published by the Matthias Corvinus Society of Budapest from 1921 to 1944.

The protagonist of the development of Fiume in this period was Giovanni de Ciotta (1834-1903), who led the city as Podestà from 1870 to 1896. A firm supporter of municipal autonomy and the link between Rijeka and Hungary, he did his utmost with energy and intelligence for the economic, social and cultural development of the city. Philanthropist and man of culture, in addition to the construction of the aqueduct that took its name from him, he promoted the construction of the new Municipal Theater (Verdi Theater today Zajć) and a rational urban arrangement of the city.

It should also be remembered that Opatija definitively established itself as an international tourist centre. In 1885 Opatija – which, although only 13 kilometers from Rijeka, was located in the Austrian part of the Monarchy – had become the “Austrian Nice”, a famous health resort frequented by the high society of all Europe.

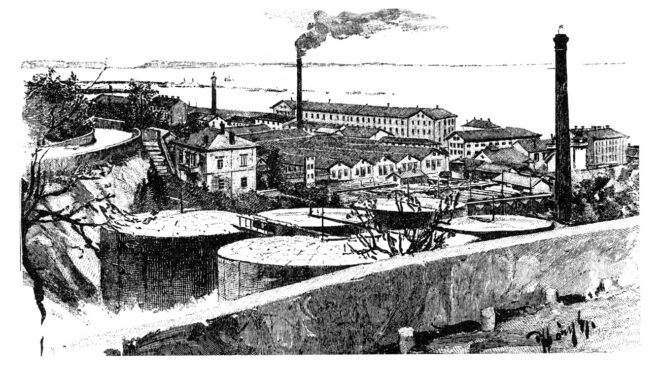

Rijeka – The mineral oil refinery in 1883

10. "THE MOST BEAUTIFUL PEARL IN THE CROWN OF ST. STEPHEN"

“Rijeka, the most beautiful pearl in St. Stephen’s crown”: this was a recurring name in the publicity and speeches of Hungarian politicians of the time, aimed at emphasizing the fundamental importance of the city for Hungary at the time.

From 1869 to 1913 the population increased from 17,884 to 48,492 souls, thus increasing by 178%. According to the census of 1900, out of 38,955 inhabitants there were 17,305 Italians, 9,092 Croats and Slovenes; 12,558 Hungarians, Austrians, Jews and others.

The expansion of the port began on 18 February 1872: within nine years Rijeka had a port that in terms of size, equipment, warehouses for goods and railway connections could compete with the large European ports. From 1870 to 1913 the surface of port waters increased 10 times: in 1913 it was 62.2 hectares. The number of incoming and outgoing ships increased from 5,549 to 19,051 and their tonnage from 261,488 to 5,791,272. On the eve of the Great War, Fiume was the eighth port in Europe.

The extraordinary economic take-off of the city is also documented by the development of shipping companies, in which the Rijeka entrepreneur Luigi Ossoinack played a fundamental role. At least the Hungarian-English shipping company Adria should be remembered, which, founded in 1881, had its operational headquarters in Rijeka. In 1870 the Hungarian maritime navigation had only one steamer belonging to the port of Rijeka, in 1915 as many as 135 units.

Alongside the existing industries, new industrial realities of European importance arose, including the rice husking plant and starch factory (1881), the largest in the Empire, the Danubius shipyard (from 1911 Ganz-Danubius), the Oil Refinery (1882) and the torpedo factory.

The torpedo factory was founded in 1875, under the name Torpedofabrik Whitehead & Comp., by the Englishman Robert Whitehead (1823-1905), who transformed an invention of Giovanni Biagio Luppis (1816-1880) from Rijeka – the “save-coast”, a motor boat loaded with explosives to be directed against enemy ships – into a deadly device capable of moving under the surface of the sea. The perfected device became the modern torpedo, determining the advent of ships called torpedo boats, which launched the “torpedoes”, and providing the submarine, born from the end of the eighties of the century, with the decisive weapon. In 1881, Whitehead’s factory sold over 1,000 torpedo boats to several states, including England, Russia, and France.

Speaking of Giovanni de Ciotta, we have already mentioned the urban and architectural development of the city. Several famous architects worked in Rijeka: the Viennese Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, the Trieste Giacomo Zamattio, the Hungarians Ferenc Pfaff, who built the railway station, and Lipót (Leopold) Baumhorn, who built the great Synagogue, later destroyed by the Nazis, and above all Alajos Hauszmann who completed the Renaissance-style construction of the new grandiose Governor’s palace in 1896.

In 1914, the Fenice cinema-theater was built in Secession style and with a futuristic reinforced concrete structure, designed by the architects Theodor Träxler, from Vienna, and Eugenio Celligoi, from Rijeka, now unfortunately abandoned.

The most important artist of the period is Giovanni Fumi: born in Venice in 1849, he was active in Rijeka from 1883 to 1900, where he carried out decoration work in various public buildings and painted frescoes, altarpieces and portraits.

The Rijeka moors of the goldsmith Agostino Gigante had great fame and European diffusion who, taking up a Venetian tradition, made small jewels, applying on brooches, bracelets and necklaces Moor’s heads with the head and turban covered, respectively, with black and white enamel.

A sign of the great cultural progress of the city was the opening of the Civic Library in 1893 and the birth of new important associations, including the Society of Artisans (1869), whose president was the publisher and historian Emidio Mohovich, the Philharmonic-Dramatic Society (1872), which had among its members the most important personalities of the city’s cultural, economic and political life, and the Literary Circle (1893) which invited the leading Italian writers and writers of the time to hold conferences in Fiume and published two periodicals, La Vita Fiumana and La Vedetta. Among the sports associations are the Eneo Nautical Society (1892) and the Rijeka Alpine Club (1885) which had the historian Egisto Rossi and the naturalist Guido Depoli among its animators and its press organ in the magazine Liburnia, which is still published today in exile.

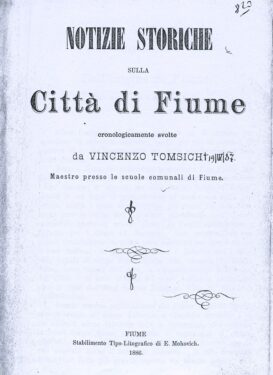

This was also the period of the flowering of Rijeka historiography. In addition to Emidio Mohovich, who left us a valuable work on the Croatian period (Rijeka in the years 1867 and 1868) published in 1869, we must mention Vincenzo Tomsich (? – 1887) author of the first history of Rijeka, published in 1886 with the title Historical news on the city of Rijeka, a volume full of documents often reproduced in full.

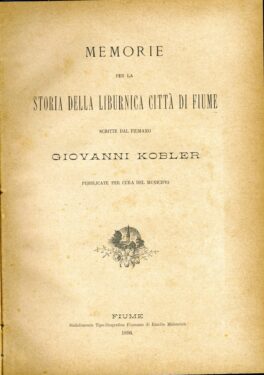

Memoirs for the history of the Liburnian city of Rijeka is the title of the three-volume work by the great scholar Johann Kobler (1811-1893). The work, a masterpiece of positivist historiography and a monument to the autonomy of Rijeka, was published posthumously in 1896 by the City Hall by Aladár (Alfredo) Fest, a Hungarian-Rijeka historian, author in turn of fundamental works on the history of the city

Part of Fest’s essays were published in the Bullettino della Deputazione fiume di storia patria, the first volume of which appeared in 1910 with a presentation by Egisto Rossi (1881-1908), a brilliant intellectual and historian who died very young. The Bullettino was published until 1921 and in 1910 it was joined by the Monuments of Rijeka history edited by Silvino Gigante.

The Croatian presence in Rijeka was also relevant in the third Hungarian period. In 1878, Erazmo Barčić founded the newspaper Sloboda in nearby Sušak, to claim the rights of Croats in Rijeka. From 1900 the Croatian politician Frano Supilo (1870-1917) also worked in the Kvarner city.

Giovanni de Ciotta (1824 – 1903) podestà of Fiume for twenty-six years in the period of the “Hungarian idyll”

11. THE CRISIS OF THE HUNGARIAN IDYLL: AUTONOMISTS AND IRREDENTISTS

In the 1990s, Hungarian politics, under the government of Dezső Bánffy (1895-1899), underwent a change in a nationalistic and centralist direction. In Hungary, as in all European countries, the ideology of nationalism was rapidly asserting itself. The new Magyar orientation led to the questioning of the special position of Rijeka defined by the Provisional and the Statute of 1872. The “Hungarian idyll” had entered a crisis.

To defend the threatened autonomy, in 1896 the Autonomous Association or Autonomous Party of Rijeka was born by a group of young people led by the brilliant lawyer Michele Maylender (1863-1911), which already achieved a resounding success in the municipal elections of the following year. Maylender was elected podestà and in his inaugural speech he declared:

The only source and root of Rijeka’s love for Hungary, the origin of the special patriotism of the people of Rijeka for the Hungarian nation, is to be sought exclusively and solely in the autonomy that Rijeka enjoys and that the government respects. If one wanted to take away from the Municipality of Rijeka the right to administer municipal affairs on an autonomous basis, if one wanted to take away the Italian language, in that case the tree of our patriotism, deeply damaged at its roots, would absolutely have to perish. One cannot imagine Hungarian patriotism in Rijeka separated from autonomy.

The battle in defense of municipal autonomy had its voice in the weekly La Difesa founded by Maylender on September 25, 1898 and the tug-of-war between the City Council and the central government lasted until the beginning of 1901, when an agreement was laboriously reached.

After being elected podestà in 1901 for the sixth time, Maylender resigned due to internal disagreements within the Party and devoted himself for a decade to the drafting of a monumental History of the Italian Academies in five volumes (it was published posthumously in 1926). Maylender’s resignation corresponded to the rise of Riccardo Zanella who soon became the head of the Autonomous Party and in 1905 he was also elected deputy to the Hungarian Parliament.

The opposing nationalisms were growing and undermined the structure of the Empire from within. From this point of view, the position of the Rijeka autonomists constituted an anomaly: extraneous to modern nationalism, it defended the “autonomies” of the plurinational Empire, whose political legitimacy it did not question. But the pressure of nationalism was now also being felt in Rijeka.

From 1873 to 1897 Croatian patriots had taken control of the administration of all Dalmatian cities except Zadar from the Italians. In 1900 Supilo founded the newspaper Novi List in Rijeka Frano and was one of the promoters of the Rijeka Resolution of 2-3 October 1905 in which he hoped for the union of Dalmatia, Istria and Rijeka with Croatia-Slavonia. Croatian publishing activity in the Kvarner city developed mainly through the work of the Dalmatian priest Bernardin Nikola Škrivanić who gave life to publishing houses and various periodicals.

A few months before the Supilo Resolution, in July 1905 some young Italian patriots – Gino Sirola, Armando Hodnig (Odenigo), Luigi Cussar and others – on the model of Mazzini’s Giovine Italia had founded the Circolo Giovine Fiume

Italian irredentism thus became an organized political reality in Fiume and from 6 April 1908 it also had its own press organ, the biweekly periodical La Giovine Fiume, born from the initiative of a group of “elders” who had joined the society, including Icilio Baccich, Riccardo and Silvino Gigante, Egisto Rossi, Lionello Lenaz.

The irredentists of the Giovine Fiume, although a minority, gave life to various initiatives that increased their visibility, such as the participation, together with the Florentines and the Italian irredents of Austria, in the Dante celebrations in Ravenna in 1908, but also aroused the suspicion of the authorities. In January 1910 the irredentist periodical was suppressed and on 22 January 1912 Governor Wickenburg also dissolved the association.

From 1910 to 1914 Wickenburg promoted a harsh policy of repression and Magyarization. In June 1913 the State Police was introduced into the city, in violation of the Statute of 1872, and the climate became incandescent. Some adherents of the Giovine Fiume placed a bomb on the windowsill of the Government building that only caused the breaking of many panes. A few months later, on the night between 1 and 2 March 1914, a new bomb exploded in the garden of the Government building, again without serious consequences. But it soon came to light that the attack had been organized by a confidant of the police to justify the repression against irredentists and the “inconvenient” Rijeka! The scandal was enormous. Autonomists and irredentists came closer together: on March 23 Riccardo Gigante published the single issue La Bomba, financed by Zanella, in which he accused the Hungarian police of having hatched the plot in agreement with Governor Wickenburg and asked to “be indicted in order to be able to bring the evidence of his accusation before the judges”. But there was no trial: after a few months the war broke out and in March 1915 Gigante fled to Italy.

12. THE GREAT WAR AND THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Dual Monarchy, and his wife Sofia, on an official visit to Sarajevo, were killed by the Bosnian Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It was the spark that ignited the First World War. On July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and on August 4, Germany, Russia, England, and France had already entered the war through the mechanism of alliances. All of Europe was in flames.

The attitude of Italy, which had declared its neutrality on 3 August, was followed anxiously in Fiume. The situation of the city began to be known in Italy only shortly before the outbreak of the war through La Voce di Prezzolini in Florence, in which the Rijeka Gemma Harasim and Enrico Burich collaborated. An important article on The tragedy of the Italianness of Rijeka was published on 28 August 1913 by Burich, who was joined by Icilio Bacich with several writings.

On 26 April 1915 the Pact of London was signed: in exchange for intervention on the side of the Entente powers, Italy would obtain Trentino, Alto Adige, Trieste, Gorizia, Istria up to Kvarner and a part of Dalmatia, but not Rijeka. The news of the pact, the clauses of which should have remained secret, immediately leaked out also in Fiume and the absence of the city from the list of transfers promised to Italy also leaked out.

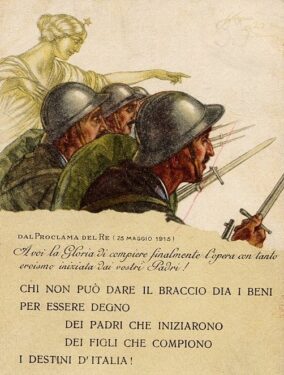

On 23 May 1915 Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary and on the 24th Italian troops vacated the Piave border.

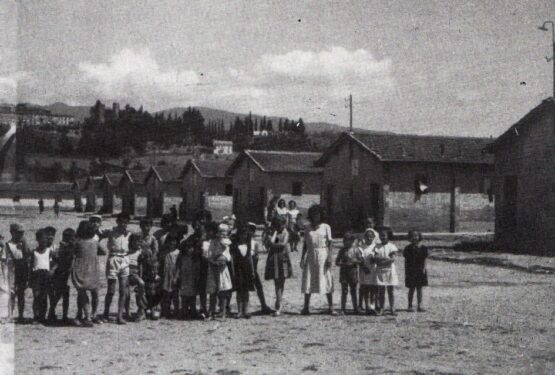

Numerous Rijeka had already been called up to arms and sent to fight in Eastern Europe against the Russians in Galicia and Bukovina. Many others, suspected of harboring pro-Italian sentiments, were interned in the Hungarian camps of Tápiósüly and Kiskunhalas; the authorities responded to the protests of the podestà Francesco Gilberto Corossacz with the dissolution of the Municipal Council. In Tápiósüly, today Sülysáp, about 800 civilians of Italian nationality were interned, almost all from Rijeka. Political dissidents from Rijeka, including Francesco Drenig, Attilio Depoli, Guido Depoli and Luigi Cussar, were confined to Kiskunhalas.

Between the summer of 1914 and the spring of 1915 more than one hundred young people from Rijeka fled to Italy to enlist as volunteers: 9 fell in battle, 6 died of war, 55 were decorated, 24 were sentenced to death in absentia for high treason by the Austro-Hungarian authorities. Mention should be made of the brothers Baccich (Bacci) – Icilio (1879-1945), Iti (1892-1954) and Ipparco (1890-1916), who died in combat – and the fallen Mario Angheben (1893-1915) and Annibale Noferi (1895?-1916), who, having emigrated to Brazil in 1912 at the outbreak of the war, had returned to Italy to enlist as a volunteer. Riccardo Gigante, sheltered in Italy in 1914, remained at the front as a volunteer for the duration of the conflict, contributing to war propaganda. Giovanni(Nino) Host (later Host-Venturi) (1892-1980), who had also taken refuge in Italy since 1911, was wounded twice and awarded three silver medals.

Among the volunteers of autonomist origin we find Zanella’s closest collaborator Mario Blasich (1878-1945): instead of asking for the exemption to which he was entitled as a doctor and protophysicist of Fiume, he enlisted and then deserted on the Russian front and, having come to Italy, lent his work as a medical captain in front-line departments. Giuseppe Sussain (1864-1921), despite being over fifty, volunteered for the Italian army and asked to be sent to the front line. Umberto D’Ancona (1896-1964), biologist and zoologist of international fame, sheltered in Rome at the beginning of the war, enlisted in the Italian army at a very young age and was wounded on the Karst. The head of the Autonomous Party Riccardo Zanella, sent to the Russian front, deserted and reached Italy, where he created the National Committee for Rijeka and Kvarner with the aim of annexing Rijeka to Italy.

From 15 to 23 June 1918 the battle of the Piave marked the defeat of the Austrians. The defeat of the Empire was now in the air. On 1 October 1918, representatives of all nationalities in the Austrian parliament affirmed their right to national independence. On 6 October, the “Plenary Council of Croats, Serbs and Slovenes” in Zabagria declared the end of all relations with Budapest, so the Croats did not intervene in the session of the Hungarian parliament on 18 October. In this session, the deputy of Rijeka Andrea Ossoinack protested vigorously against a possible annexation of Rijeka to Croatia, declaring:

[…] I consider it my implicit duty […] to raise a formal protest in this Chamber, in front of the whole world, against anyone who wants to concede Rijeka to the Croats. […] Because Rijeka was not only never Croatian, but, on the contrary, it was Italian in the past and Italian will remain Italian in the future! […] With reference to this consideration, I take the liberty, as a deputy of Rijeka, […] to make the following declaration: Since Austria-Hungary, in its peace proposal, sets as a fundamental condition the right of self-determination of peoples, proclaimed by Wilson, so Rijeka claims as a “corpus separatum” this same right for itself, and in accordance it claims to exercise in full the right of self, without any limitation, the right of self-determination of peoples.

After a few days, on 29 October, the Italian troops broke through the enemy front at Vittorio Veneto and on 3 November entered Trento and Trieste. On 4 November hostilities finally ended.

13. THE QUESTION OF FIUME AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE

October 29, 1918 was a crucial day for Rijeka. The Croatian parliament proclaimed the “Sovereign National State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs” with Rijeka and Dalmatia – which on 1 December became the “Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes” (SHS) ruled by the Karadordevic dynasty, the Hungarian governor Jekelfalussy abandoned Rijeka and the National Council in Zagreb appointed Konstantin Rojčević as commissioner for the territory of Rijeka-Sušak.

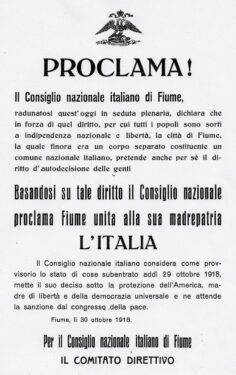

At 10 a.m. on 29 October, about sixty citizens gathered in the hall of the Municipal Council of Rijeka and the president of the assembly Antonio Grossich, a famous doctor and writer, invoked Rijeka’s right to self-determination. The assembly confirmed the podestà Antonio Vio in office, constituted itself as a city committee which assumed full powers and appointed a steering committee from among it. Fiume thus posed itself as an independent state, refusing to be considered a passive object of negotiations between the powers. In the evening the City Committee, meeting in the hall of the Philharmonic, took the name of the Italian National Council of Rijeka chaired by Antonio Grossich. The following morning the Council approved a proclamation-manifesto to be posted in the city: thus was born the Proclamation of annexation of Fiume to Italy on October 30, 1918 . Here is the text:

The Italian National Council of Rijeka, meeting today in plenary session, declares that by virtue of that right, by which all peoples have arisen to national independence and freedom, the city of Rijeka, which until now was a separate body constituting an Italian national municipality, also claims for itself the right of self-determination of the people. On the basis of this right, the National Council proclaimed Rijeka united with its motherland, Italy. The Italian National Council considers the state of affairs which took place on October 29, 1918, to be provisional, places its decision under the protection of America, the mother of universal liberty and democracy, and awaits the sanction of it from the Peace Congress.

At the same time, in the Government Building, the representative of the Zagreb Council, Konstantin Rojčević, declared that he was assuming state power over the city of Rijeka! Thus a genuine dualism of powers was created in the Kvarner city.

A large Italian demonstration took place in the early afternoon of the same 30 October: the Proclamation of annexation was read publicly and was acclaimed by a crowd of about 20,000 people. A few hours later a procession with Croatian flags, moving from Sušak, crossed the city.

The National Council urged the Italian government to intervene and so on the morning of 4 November 1918, a few hours before the armistice came into force, four Italian ships entered the port of Rijeka, welcomed by a cheering crowd. But Admiral Rainer, commander of the small fleet, maintained an equidistant attitude, conditioned by the difficult international situation. Therefore, the National Council, by sending its representatives to Italy, tried in every way to modify the attitude of the Italian Government dictated by Foreign Minister Sonnino, a supporter of a strict application of the Pact of London.

A turning point occurred on 17 November: Rijeka was subjected to an inter-allied occupation, the Croatian authorities abandoned the city and the Italian National Council became the sole body of power. The situation remained undefined, however, since Fiume had not been occupied by Italy, but by the Entente, which made an essential difference.

In the meantime, the Steering Committee of the National Council had assumed the functions of a real provisional government and Rijeka behaved as an independent state, also equipping itself with its own Constitution, the draft of which was prepared on 3 December 1918. On 5 December 1918 the head of the Autonomous Party Riccardo Zanella returned to Rijeka, but he soon came into conflict with the National Council.

At the Peace Conference, which opened in Paris on 18 January 1919, the question of Fiume proved to be an inextricable knot for the Italian government: the irreducible opponent of the annexation of Fiume to Italy was the President of the United States Wilson and England and France were also in favour of the territorial requests of the SHS Kingdom.

Meanwhile, in the Kvarner city, the tension between the population and the French military, which had already manifested itself in the previous months, exploded on July 2, 1919 with serious accidents that caused some deaths and injuries. The Paris Conference sent a Commission of Inquiry to Rijeka, which concluded its work after a month in a way that was completely unfavourable to the people of Rijeka, ordering the dissolution of the National Council and total inter-allied control of the city. Moreover, the new Italian government of Francesco Saverio Nitti, in office since June 23, seemed to consent.

In Rijeka, the aversion against the Allied powers increased, as well as the fear of being abandoned to the Croats. After all, at the end of August the Grenadiers of Sardinia, the first Italian soldiers who entered Fiume on November 17 of the previous year, had had to leave the city, accompanied – at five in the morning! – by an immense crowd.

The Peace Treaty with Austria was signed in Paris on 10 September 1919: it provided for a simple renunciation by Vienna of the territories of the eastern Adriatic and the new Italian eastern border continued to remain undefined.

14. THE RIJEKA ENTERPRISE

The disappointing results achieved by Italy at the Peace Conference contributed to the spread in Italian public opinion of the idea of the “mutilated victory”, of which Gabriele d’Annunzio, a poet of European fame and also well known as a highly decorated fighter and protagonist of a series of exceptional war actions, such as the “mockery of Bakar” of 10-11 February 1918 and the “flight over Vienna” of 9 August 1918.

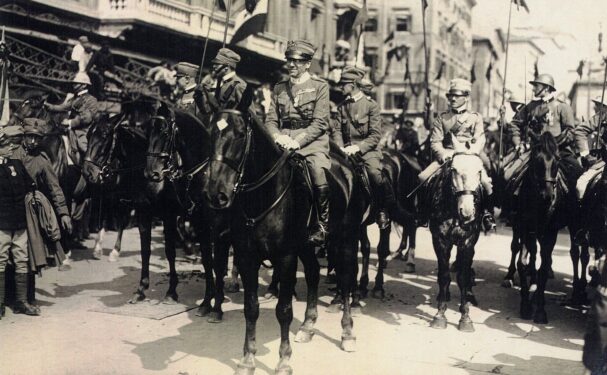

Already on 15 November 1918 d’Annunzio had assured his support to the envoys of the Rijeka National Council met in Venice. In May 1919 some officers of the grenadiers, the so-called Seven Jurors of Ronchi, forced to leave Fiume a short time before, put themselves under his orders: so on the night between 11 and 12 September 1919 d’Annunzio with a column of “Legionaries” moved from Ronchi and, without being opposed by the troops of the regular army, at noon on 12 September he entered Fiume welcomed by an overflowing crowd. The Allied forces left the city and the inter-allied command was replaced by the Italian command. D’Annunzio’s enterprise thus made Italy regain that influence in the Adriatic that the Peace Conference had denied it.

On 20 September 1919 d’Annunzio confirmed the Italian National Council in office , reserving for himself the power of control over the most important acts. Two days earlier he had met Zanella and between the two there had immediately been a profound disagreement on the prospects of the company and on relations with the Italian government, a disagreement that soon turned into an open rupture.

On October 26, 1919, elections were held for the renewal of the Municipal Council (still called the National Council) on the basis of the new electoral law which, approved a few days before the entry of the Legionaries, extended the vote to women.

The vast majority of the votes went to the National Union which grouped the parties in favor of annexation.

The Nitti government – which feared the destabilizing effect of the Enterprise for the Italian state structure shaken by a deep economic and political crisis – tried in various ways the path of compromise and at the end of November proposed to d’Annunzio a modus vivendi in which, in exchange for the withdrawal of the Legionaries, it undertook not to separate Fiume from the motherland, postponing the final solution of the question to a more favorable time.

The National Council approved the proposal, but the poet – reluctant to abandon an enterprise whose moral value went beyond the specific question of Fiume for him – opposed it and promised to resort to a plebiscite. The consultation was held on December 18, but towards evening, when the prevalence of votes in favor of acceptance was outlined, d’Annunzio suspended the counting and the following day justified himself with a speech in which he opposed the “sad ballot boxes” of the elections with the real “inexhaustible ballot box” of the “heroic soul” of the Fiumani.

The events of December 1919 marked the beginning of a second phase of the Enterprise. The intransigent and revolutionary component of D’Annunzioism came to the fore: on 20 January 1920 the revolutionary syndicalist Alceste de Ambris became head of the Commander’s cabinet, republican ideas and social palingenesis spread in some legionary circles, the weight of futurists such as Mario Carli increased.

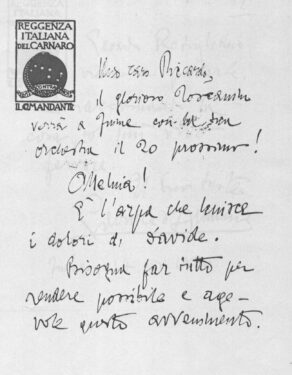

On 8 September 1920 d’Annunzio solemnly proclaimed the Italian Regency of Carnaro, a provisional State of Fiume awaiting annexation to Italy, and promulgated the Carta del Carnaro, the new constitution of the city drawn up by De Ambris and revised by the poet. Fiume became, with the poet’s expression, the “City of Life”, a sort of experimental society, with new ideas and values, often transgressive with respect to current morality and politics.

All this had the effect of disorienting the moderates, arousing concerns within the National Council and arousing defections even among the soldiers who came to Fiume with d’Annunzio.