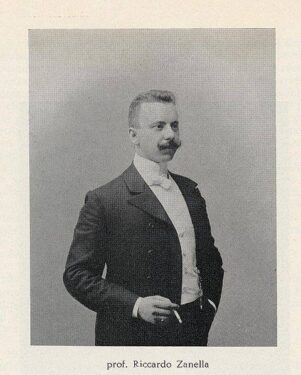

RICCARDO ZANELLA

End of the Hungarian Idyll and the birth of the Autonomous Party in 1896.

By 1895, the idyll with Hungary was practically over. The industrial development that took place in the city thanks to the enlightened work of the podestà Giovanni de Ciotta, who had been able to mediate with the government of Budapest, had not created the basis for a lasting political coexistence. At the end of the nineteenth century, the new differences between the Budapest government and the Rijeka municipality were not limited only to the political and administrative field, but also found an outlet in the context of national claims. The break occurred when the Hungarian government began to issue measures aimed at limiting the autonomy of Rijeka. In 1896 the Autonomous Party was founded by Michele Maylender, who was shortly thereafter elected as the new podestà of Rijeka. Maylender's election was the decisive signal of the political change underway. The newspaper of the autonomists "La Difesa" was in the hands of Riccardo Zanella, the future great protagonist of the Rijeka autonomist movement. "La Difesa", to avoid Hungarian censorship, was printed in Sussak (Croatian territory subject to other regulations) and was smuggled into Rijeka. The people of Rijeka further developed, in this period, a strong identity based on their autonomous history and the Italian language, despite the fact that each of them boasted multiple ethnic origins in the family. The Rijeka dialect, commonly spoken in homes and squares, was a direct emanation of the Venetian dialect and this was already enough for the Rijeka people to define their centuries-old identity. Politically, Italy was too weak to represent a pursuable political reality and a real irredentism was born, as we will see in the early years of the 20th century. The Rijeka community felt protected only through a wide municipal autonomy possible within a supranational structure and the Italian language was an indispensable factor. The development of irredentism and the concept of nationality on the eve of the First World War undermined the old autonomist system not only in Rijeka, but also in the neighboring Istrian and Dalmatian territories.

The eve of the First World War and national issues

After the birth of the Autonomous Party, following a season of national contrasts with Hungarians and Croats, the Mazzinian-inspired circle "La Giovine Fiume" was born in Rijeka in 1905 with Luigi Cussar, Riccardo Gigante, Gino Sirola and other exponents at its head. It was a response to the famous "Rijeka Resolution" (Riječka Rezolucija) of 3 October 1905, with which some Croatian parties led by Frano Supilo called for the union of the city with Croatia. The new national tensions between Italians, Croats, Hungarians and Serbs began to put in serious crisis not only the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also the very political and identity concepts on which Rijeka's autonomy was based. The contrasts between the young Italian irredentists multiplied, not only with the Croats, but also with the autonomists of Maylender and Riccardo Zanella. The Italian intervention in the First World War, which began on 24 May 1915, prompted more than a hundred people from Rijeka to flee, who volunteered to join the army of the Kingdom of Italy. Most of the Rijeka, however, were recruited into the Hungarian divisions of the Honved and sent to fight against the Russians in the regions of Galicia and Bukovina. In Fiume, Italy's entry into the war fueled new, more radical political ideas in a pro-Italian sense. The fact that Italy with the Secret Pact of London (April 26, 1915) had not asked for the port of Fiume, in the event of victory, will produce serious consequences at the end of the war. In 1915, the Hungarian police organized a roundup of citizens suspected of harboring Italian feelings, who were deported to the Hungarian internment camps of Tapiosuly and Kiskunhalas. During the war years, all political action in the city had substantially cooled down. The Italian irredentists such as Riccardo Gigante, Gino Sirola, Antonio Grossich, Luigi Cussar, Carlo Conighi, Armando Odenigo etc. either fought in the Italian army or had been deported to Hungary, while the autonomists Riccardo Zanella and Mario Blasich, enlisted in the Honved, had voluntarily surrendered to the Russians. With the end of the war and the defeat of Austria-Hungary, a long political battle began for Rijeka for the political and state belonging of the city. In those very problematic post-war years, Riccardo Zanella's idea of creating an independent Rijeka State that would play a mediating role between the Kingdom of Italy and the new State of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes gradually came to life and strength. In Zanella's project, the Croats of Rijeka found space for the first time.

End of the First World War. Autonomous river or Fiume d'Italia? Contrasts between autonomists, annexationists and D'Annunzio

Even before the end of the conflict on 18 October 1918, the Rijeka deputy Andrea Ossoinack in the Budapest parliament raised a solemn protest following the assignment of Rijeka by Charles I of Habsburg to the new southern Slavic regions, emphasizing the autonomy of Rijeka and its Italianness. With the defeat of Austria-Hungary, everything foreshadowed the passage of Fiume to the State of the Serbs-Croats-Slovenes, since with the already mentioned, secret pact of the Pact of London, Italy in the event of victory had asked for Istria and part of central Dalmatia, but had renounced to ask for Fiume. On October 30, 1918, the people of Rijeka, gathered in the Italian National Council chaired by the doctor Antonio Grossich, took to the streets and with a proclamation demanded, on the basis of the principle of determination of peoples, wanted by the American President Wilson, the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, since the National Council of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes without the consent of the population of Rijeka had occupied the Government Palace on October 29, appointing its own president, the lawyer Rikard Lenac. The figures of the census of the population of Rijeka at that time were in favor of the Italians and on this basis the political option of the Italian National Council gained more and more strength, which obtained the support of the Italian soldiers who arrived in the city on November 4, 1918 and later also the recognition by the Inter-Allied Occupation Command, while the Croatian National Council had to move to Sussak. At the Paris Peace Conference the position of the Italian government was weakening with regard to territorial aspirations in Dalmatia and Fiume. The British, American and French allies did not agree to grant the Italians great influence in the Adriatic. In this phase, the Rijeka autonomist project became visible again, when on 5 December 1918 the leader of Rijeka autonomism Riccardo Zanella returned to Rijeka after an adventurous trip, who still enjoyed many sympathies and some government support in Rome. Zanella gave a speech on 12 December 1918 at the "Fenice" theatre, during which he proposed, albeit timidly, to the governments of the victorious powers the will of his movement to ask for independence for Rijeka. Zanella was given a written proxy to represent Fiume in Rome and Paris where the peace conference was to be held starting in January 1919. After a long period of uncertainty, on 10 September 1919 Italy signed the peace treaty with Austria without obtaining precise guarantees on Fiume and the Dalmatian territories. In this context, on 12 September 1919, the action of Gabriele D'Annunzio matured, who entered Fiume with over a thousand legionaries, after being invited to action, during the spring of 1919, by important personalities of the Italian National Council of Fiume. D'Annunzio's revolutionary program, full of social content, never met with the favor of the governments of Rome, which began to favor the political option of Riccardo Zanella and, therefore, to favor the creation of an autonomous buffer state, which would have been able to satisfy the Allies and silence the revolutionary thrusts of D'Annunzio who in response founded the Italian Regency of Carnaro. Gabriele d'Annunzio had to measure himself in those agitated junctures, not only with Mussolini and other Italian politicians, but also with the Rijeka autonomism led by Riccardo Zanella who, to be honest, had initially sided with d'Annunzio.

Birth of the Free State of Rijeka and its dramatic conclusion. Zanella's first exile.

The Autonomous Party had been, before the world war, the intransigent defender of the Italian identity of Rijeka, threatened by Hungarian politics especially at the beginning of the twentieth century and by Croatian annexationist aims. On 12 November 1920, a treaty was signed in Rapallo, between Italy and Yugoslavia, which provided for the birth of an independent Rijeka state with the support of the victorious powers. D'Annunzio did not accept the postulates of Rapallo and rejected the intimation of the head of government Giovanni Giolitti to abandon Fiume. Dramatic clashes broke out between D'Annunzio and regular Italian soldiers on Christmas days, at the end of which there were 55 deaths. D'Annunzio was forced to surrender and had to leave Fiume. On 5 January 1921, still with D'Annunzio in the city, a provisional Rijeka Government was formed, which had the task of organizing the elections of the Constituent Assembly of the new Rijeka State. In this period, groups of nationalists and fascists from Trieste flocked to the city who wanted to influence the Rijeka electorate by any means. In Rijeka, the "National Bloc" headed by Riccardo Gigante was formed with the program of claiming annexation to Italy, in opposition to Zanella's Autonomous Party, which availed itself of the strong support of the government of Rome and the Yugoslav government in favor of the buffer state. The Constituent Assembly of the new state represented only the annexationist part and not the Autonomous Party, the other minor parties such as the Patriotic League of Rijeka Indeficienter. Furthermore, the exodus of the legionaries was partial and this fact did not favor the autonomists. Nevertheless, the people of Rijeka gradually became convinced that free Fiume could achieve great economic prosperity, which was not possible in the event of annexation to Italy, as the city would have become one of the many Italian ports and moreover peripheral. In addition, the autonomists managed to propose a social program that would gain the support of the Croatian minority in the city. For all these reasons, the Autonomous Party won the elections of April 24, 1921 with a landslide victory, out of 9,554 voters 6114 votes went to the Autonomous Party (also obtaining consensus from the Croatian side) to the National Bloc went 3,440 votes. However, if we consider only the votes of the Italian ethnic group, the difference between autonomists and annexationists was not so considerable. Despite the favorable election result for Zanella, tensions and clashes continued to occur in the city between the different factions. Already after the counting of the ballots, the squads took place led by Riccardo Gigante who set fire to the ballots, but the minutes had already been drawn up and therefore the electoral vote in favor of the Free State had been reconfirmed. Zanella was even forced on April 27 to flee with his collaborators to Bakar under the protection of the Yugoslav government because of death threats received from the annexationists. On 26 June, the massacre of Porto Baross took place, where some former D'Annunzio legionnaires rose up to prevent the cession of the important port basin to Yugoslavia established by the Treaty of Rapallo. After the clash with the carabinieri and a cordon of Alpini, seven people were killed, including four legionnaires, two young students and a woman. Many were injured, at least twenty Only on 5 October 1921 did General Luigi Amantea manage to install the Rijeka Constituent Assembly, which appointed Zanella head of state and government of Rijeka. The new government formally failed to operate and the stability of the small state faltered immediately after a few months. Following the killing of the young legionnaire Fontana probably caused by the autonomists, on March 3, 1922 Trieste irredentists, republicans and former legionnaires led by the head of the Trieste fascist party Francesco Giunta, overthrew Zanella's government with weapons. There were three deaths on the Italian side and three deaths on the autonomist side. Many were injured. The city plunged into a new climate of instability and uncertainty. The autonomists took refuge in Portorè (Kraljevica) in Yugoslavia, determined not to want to cede the Rijeka government to the annexationists. After alternating events, on April 5, 1922, Prof. Attilio Depoli was appointed by the Italian military council and by what remained of the Constituent Assembly to exercise administrative powers over Rijeka. Riccardo Zanella never returned to Rijeka after those tragic events, he remained in Belgrade for a decade protected by King Alexander and then went to France. The rest of the autonomists returned to the city, but they no longer had any political weight. A few years later, on 27 January 1924, Fiume was annexed to Italy under Mussolini's government. There was no more talk of autonomy in Rijeka for a long time.

The Second World War, the ephemeral rebirth of the autonomist movement in Rijeka crushed by the Yugoslav secret police. Zanella's second exile in Rome.

Only during the Second World War, with the approach of the defeat of Italy and Germany, did the Rijeka autonomist movement rise clandestinely. Riccardo Zanella was in France, collaborating with the anti-Nazi Resistance, and towards the end of 1943, through the autonomists who remained in Rijeka Mario Blasich and his faithful companion, Giovanni Stercich, Nevio Skull, the ideas of creating a new Free State in Rijeka resumed their views. There were also meetings with the Yugoslav Resistance, but they did not absorb positive effects of collaboration. The battle to conquer Rijeka at the beginning of 1945 was very bloody for all sides. Other political organizations, such as a so-called National Liberation Committee headed by Antonio Luksich-Jamini and another Rijeka Committee of autonomist inspiration, had no serious possibility of action at that time. The situation in the field of anti-fascism in Rijeka was firmly in Yugoslav hands. On 3 May 1945, after a long battle of several months, the first units of the Yugoslav Fourth People's Army entered Rijeka. On the morning of May 4, news began to spread that during the night there had been raids by the Yugoslav secret police of the OZNA led by local elements in many homes of private citizens. The period of terror and intimidation against the Italians had begun. It became known that some exponents of the old Zanellian autonomist party, such as Mario Blasich, Nevio Skull, Giuseppe Sincich, had been killed; there was no more news of Senator Icilio Bacci, while the other Senator Riccardo Gigante had been taken and taken together with other unfortunate people to Kastav, to be then shot and slaughtered with bayonets. In those sad days, hundreds of people from Rijeka were arrested and made to disappear by the Yugoslav communist system: the former mayor Carlo Colussi and his wife Nerina Copetti, the headmaster Gino Sirola, the teacher Margherita Sennis, the anti-fascist republican Angelo Adam with his entire family, and many others disappeared victims of terror. Over a hundred police officers and dozens of financiers and carabinieri were killed and probably thrown into the existing foibe near Grobnico and Costrena. The end of the large summary liquidations in Rijeka in Istria took place only in the late autumn of 1945, and the international reaction against the violent purge carried out by the Yugoslav secret police (Ozna) was of no avail. He never paid anyone for these crimes. Some Italians belonging to the Yugoslav People's Liberation Movement also lashed out against the autonomists. This is what Lucifero Martini wrote. under the pseudonym of Lauro Chiari. in the Voice of the People of December 6, 1945 in an article entitled "AUTONOMISM AND NEOFASCISM:... while neo-fascism is developing in Italy, in our city there lives, with the same equal characteristics, a direct derivative of it: autonomism... and continues... Autonomism gathers behind it all the fascists in Rijeka and outside Rijeka who have not been hit by popular justice... In Rijeka and its surroundings at the end of the war, over 650 Italians were killed without a trace (data from the Italian-Croatian research by A. Ballarini and M. Sobolevski – The victims of Italian nationality in Rijeka and surroundings 1939-1947). The whole of Venezia Giulia was affected at that time by the Yugoslav massacres and it took the intervention of the Allies in Trieste, Gorizia and Pula, to prevent further massacres and violence against the Italian element. In this troubled period Zanella was exiled in Italy under the protection of the Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi and put himself at the head of the "FIUME" Office. From 1945 to 1956 as many as 38,000 people from Rijeka had to leave their city and seek shelter in Italy. A few thousand Rijeka exiles continued their existence abroad (Canada, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, etc.). Despite the efforts of Zanella and a part of Italian diplomacy, every attempt to revive the Free State foundered in thin air. Zanella died, in his second exile in Rome, in poverty on March 30, 1959, forgotten by all. For any in-depth study of these historical periods that can be connected with the autonomy of Rijeka, within the Society of Rijeka Studies, I recall that Amleto Ballarini, former president of the Society of Rijeka Studies, wrote a biography "Riccardo Zanella. The anti-D'Annunzio in Fiume" in 1995, in addition to several essays, Ballarini organized a conference in Trieste in 1996 entitled "The autonomy of Rijeka and the figure of Riccardo Zanella". I participated in that conference with a report entitled "Rijeka Autonomy in some Croatian historians after the Second World War". Finally, the magazine of Adriatic studies FIUME, has published dozens of articles over time on the autonomy of Rijeka and the current president Giovanni Stelli has composed a "History of Rijeka" where Zanella and Rijeka autonomy are widely discussed.

Edited by Marino Micich

Director of the Historical Museum Archive of Rijeka